ACTIVITY

Childhoods in a World at War 1939-1945

- Digital Exhibition -

© Réseau Canopé – Musée national de l’Education (1979.09324.33)

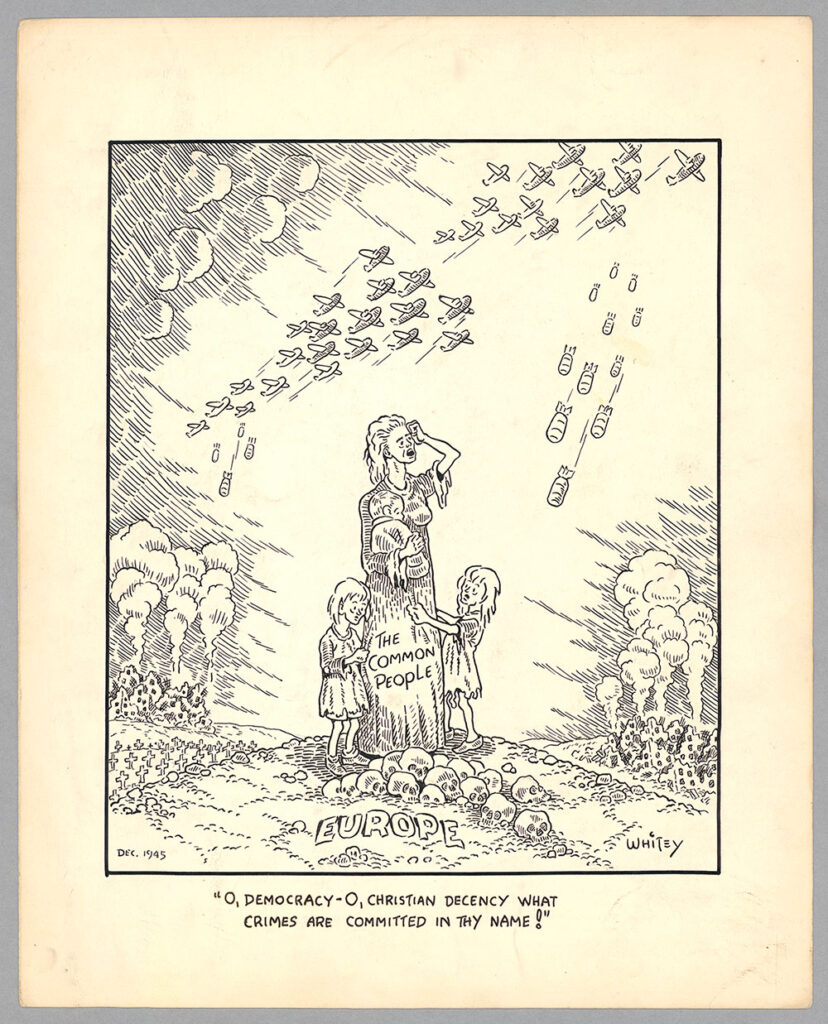

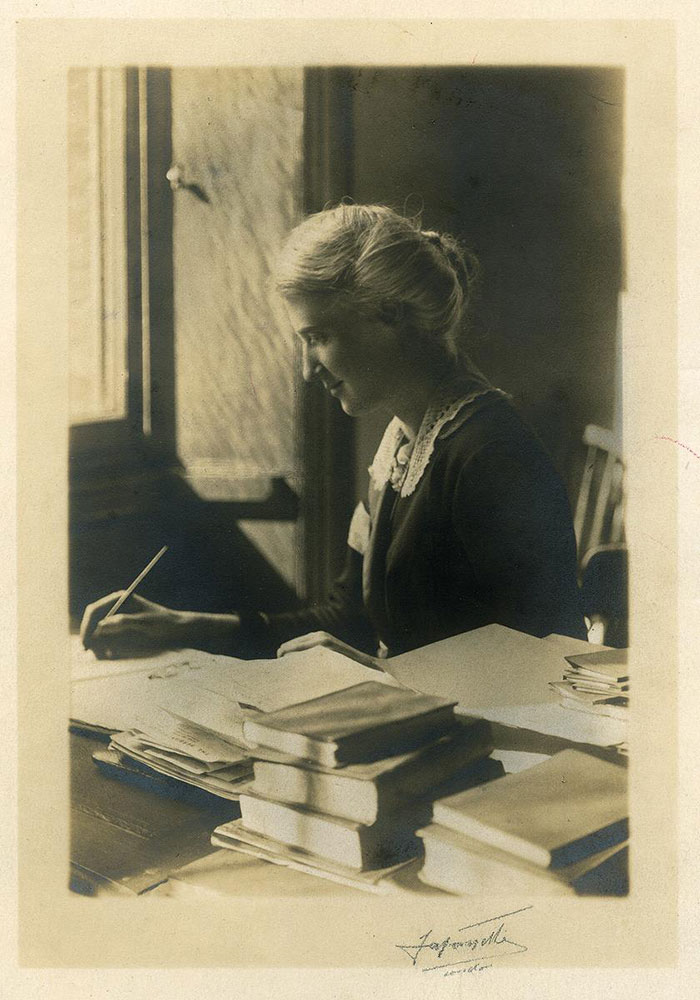

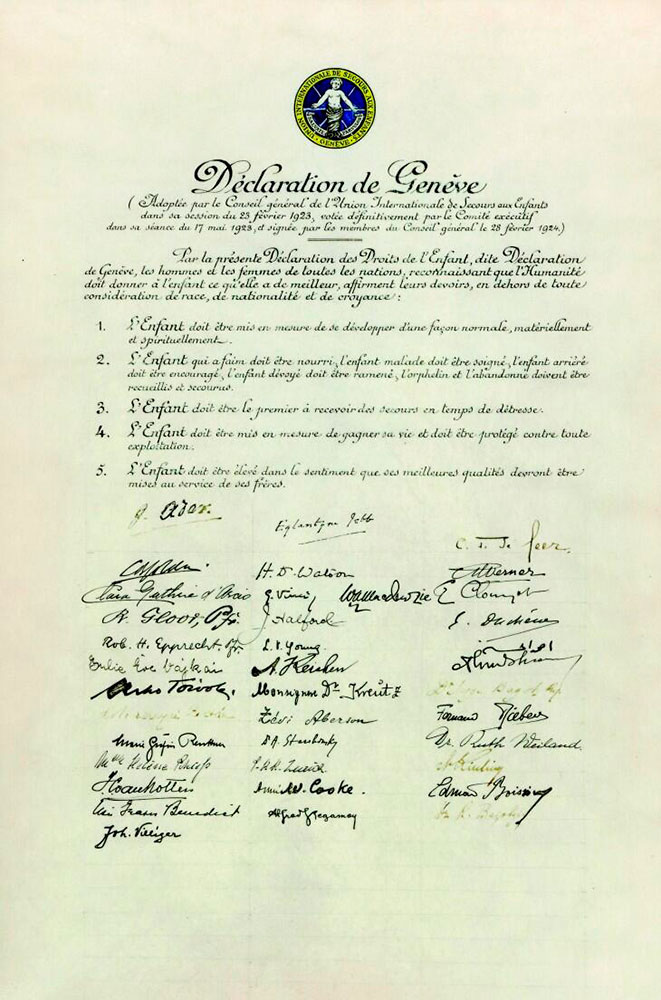

More than 100 years ago, the founder of Save the Children and fighter for the safeguarding and protection of children and their rights, Eglantyne Jebb, said:

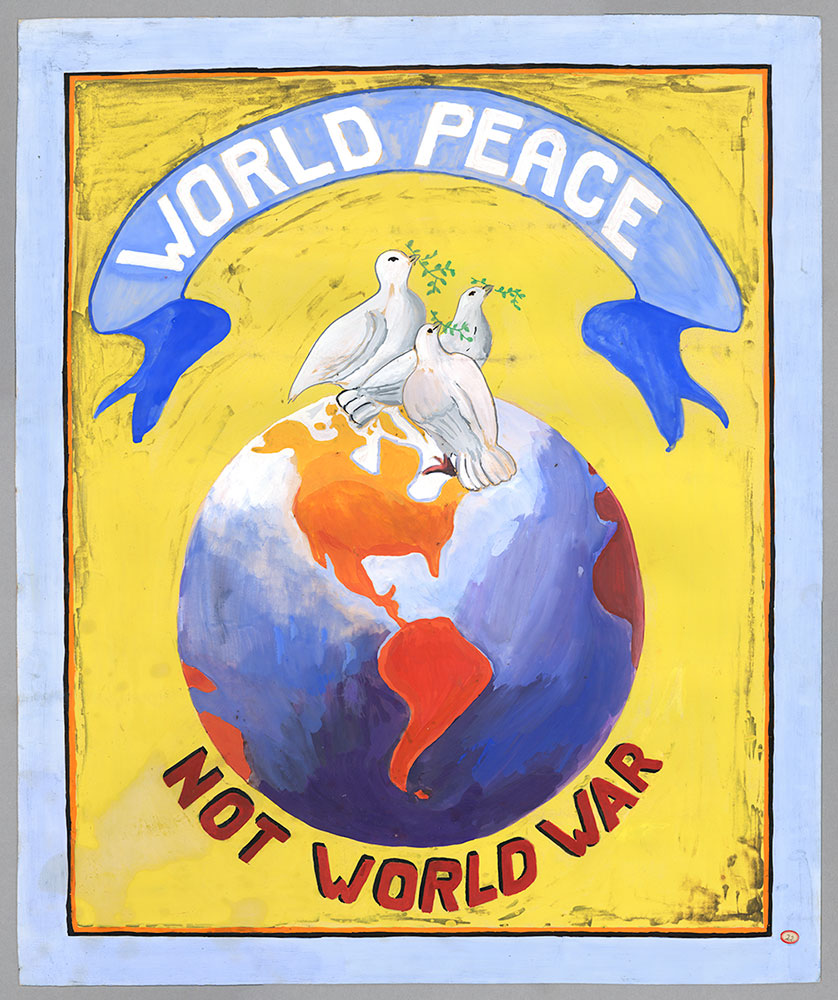

Her words have held the same force throughout the 20th century and the present, witnesses of conflicts that have claimed millions of victims among combatants and non-combatants. Since 1914, wars have become an increasingly atrocious experience both on the front lines and in the rearguard. And in them, the most vulnerable and defenceless segments of the civilian population – women, the elderly and children – were and continue to be protagonists, witnesses and victims.

In the context of armed conflict, the Second World War (WWII) represented the zenith of violence against civilians and, in particular, against children. World War II marked an entire generation of children on five continents. Their desires for a lasting peace after the disasters of the Great War were aborted on September 1, 1939, with a war that had multiple impacts on their lives and memories. Gena Yushkevich was 10 years old at the outbreak of WWII, which shortly thereafter ravaged her native country, the USSR. Interviewed by Svetlana Alekseyevich, she recalls how shocked she was when she first saw death: “I woke up in the morning…. I wanted to jump out of bed, then I remembered: it’s war, and I closed my eyes. I didn’t want to believe it.”

This exhibition offers an overview of children’s experiences during World War II and its lasting effects on childhood, while at the same time demonstrating the importance of peace for the present and the future through stories and examples from the recent past. From 1939 to 1945, millions of children experienced a radical transformation of their daily lives, lived through the war on a daily basis, tried to survive its horrors and took on responsibilities that did not correspond to their age.

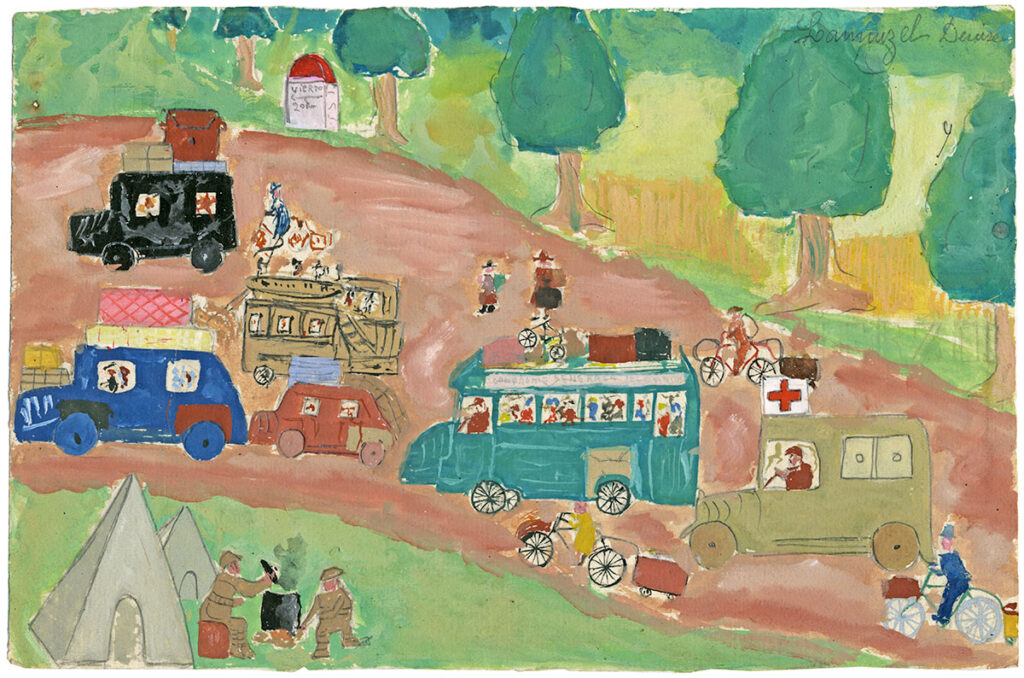

Wartime scenarios represented a violation of the 1924 Geneva Declaration on the Rights of the Child, a historic text on Human Rights, promoted by the aforementioned Eglantyne Jebb. Through these panels, we reflect collective stories of children whose lives were characterized by educational and schooling difficulties, hunger, rationing, evacuations and separation from their families, bombings, deportation, forced labour, extermination or their participation on war fronts or as resistance fighters. These traumatic events represent black holes in the memory of our societies that we must not forget in the face of the dramatic repetition that we still witness today

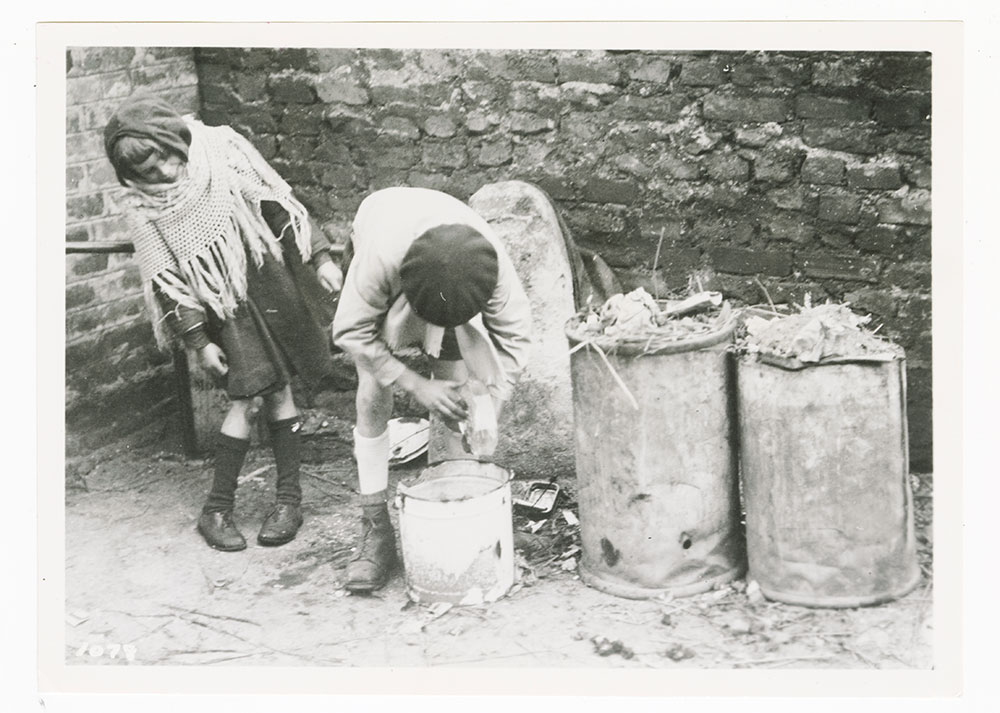

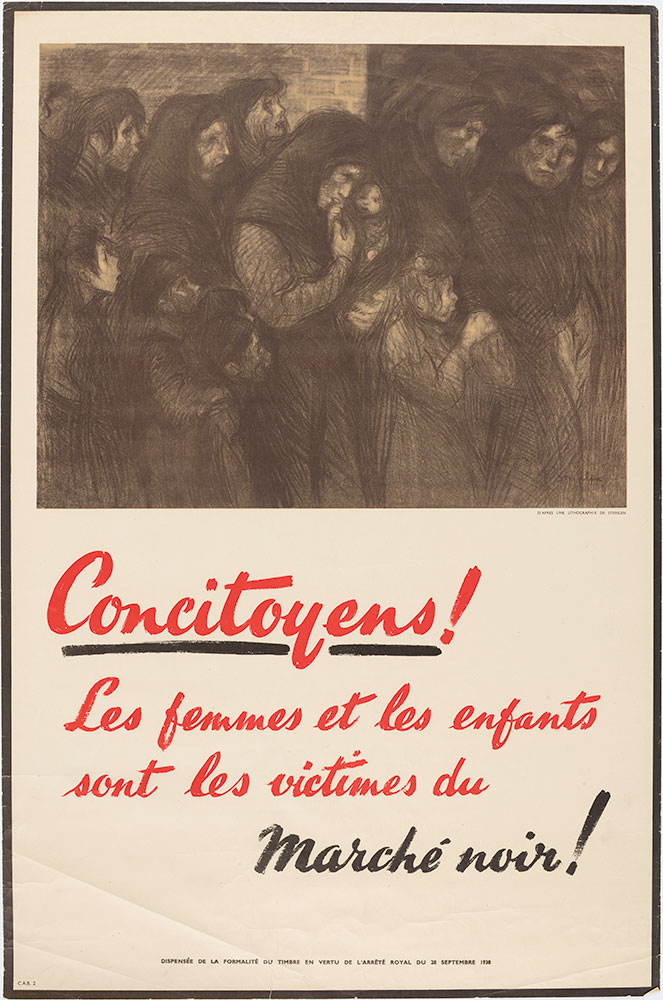

Evacuations, the departure of men to the war front, deportation, disease and bombing meant that many children and teenagers found themselves on their own. Some had to engage in hunger-driven theft and robbery, such as the petty dealers in the Warsaw ghetto, the szmugler. In particularly famine-stricken areas such as Greece, looting and smuggling of staple foods intensified. The authorities cracked down hard on the black market and propaganda warned of its consequences. Practices such as the collection of gunpowder for the ammunition trade were also dangerous: in Italy at the end of the war, there were 15,000 mutilatini, “little mutilated ones”.

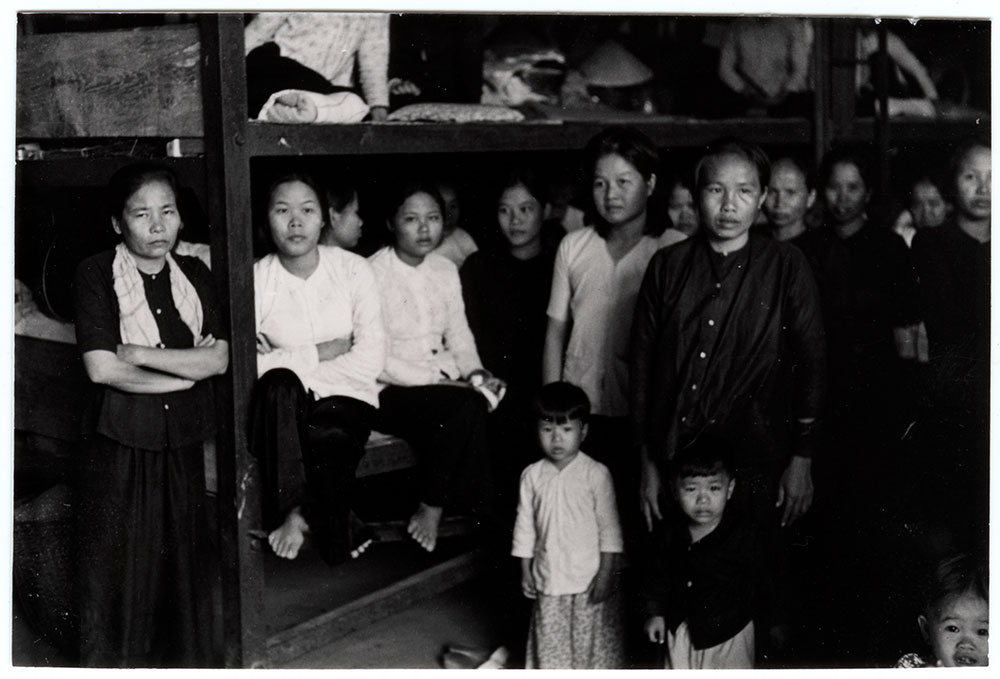

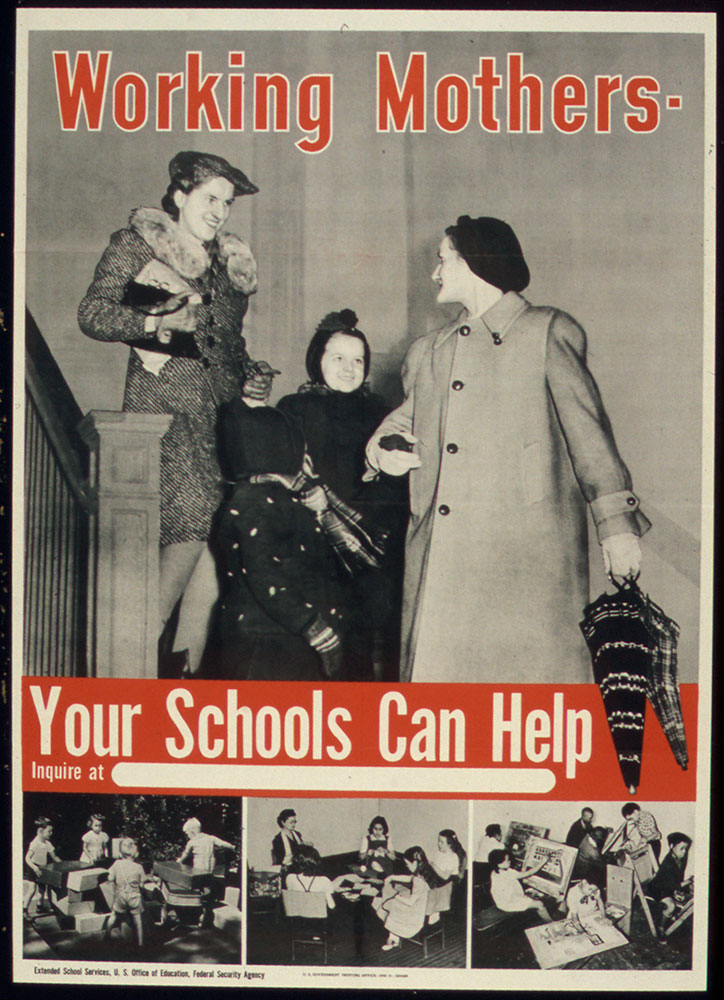

The absence of the male figure meant that many women raised their children alone, which sometimes posed a problem of reconciling work and family life in a context of a high rate of female extramarital employment. To this end, women’s support and childcare networks were created. In some countries, public day-care centres were provided for working mothers in the war industry. In 1942, a conference on “child care and the war” was held in Australia, where the Commonwealth funded day-care centres for school-age and pre-school children. In the United States, the Lanham Act of 1940, which made possible a series of social programs during the war years, subsidized the care of between 500,000 and 600,000 children of working women.

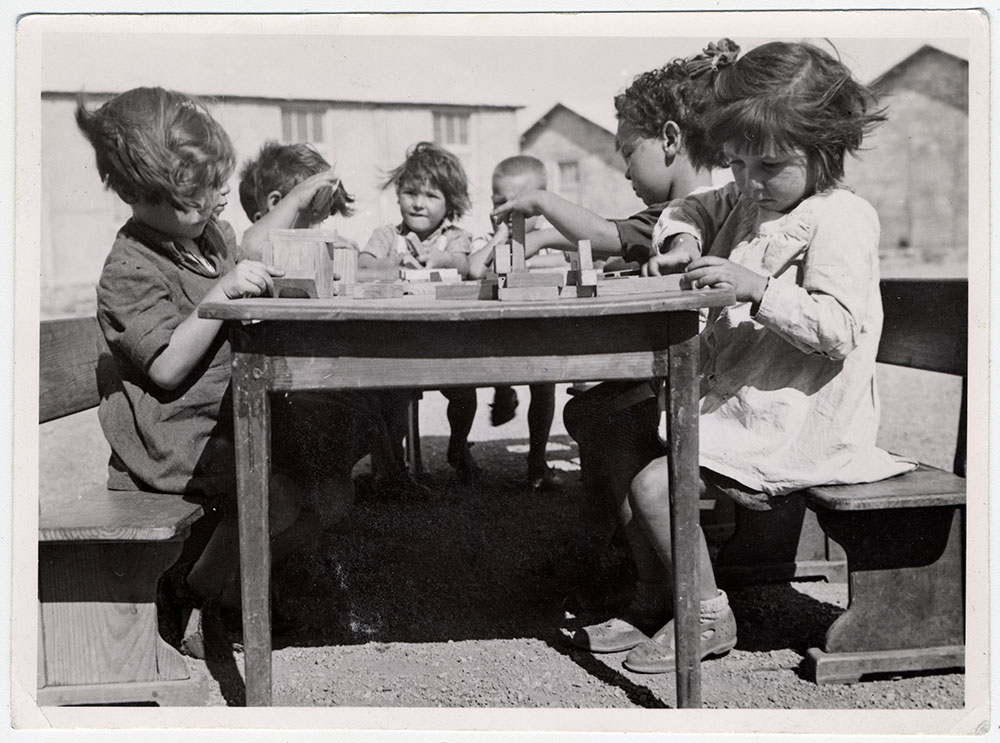

In this context, being able to do “children’s things” such as playing or going to school were real oases. The aid organizations were aware of this and tried to provide spaces for play and disconnection from reality, as did the totalitarian regimes, for example with the celebration of the fascist Befana in Italy in the occupied territories.

It became common to “play at war”. Figurines inspired by the leaders and armies of each country were marketed and games based on the exercise of power were developed, for example, imitating the attitude of the kapos in the Auschwitz camp. Likewise, governments were aware of the propagandistic use of games, songs or children’s literature as a form of indoctrination.

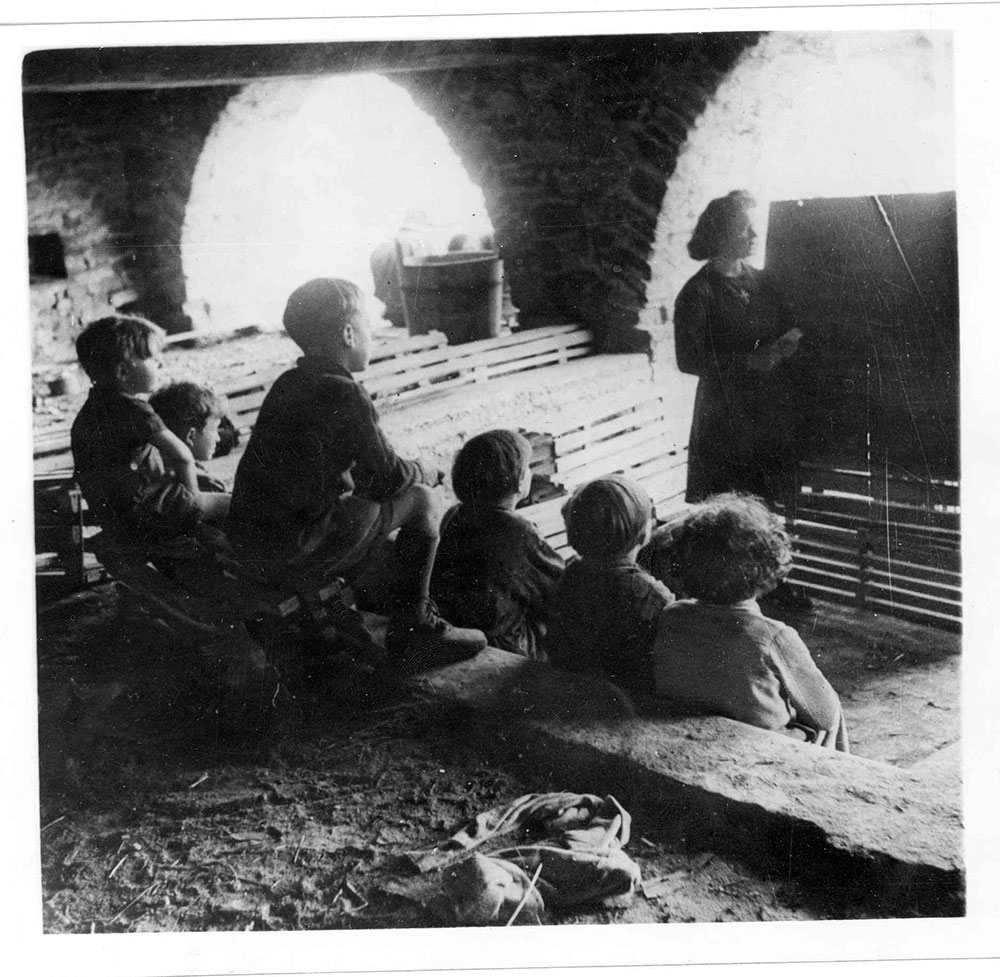

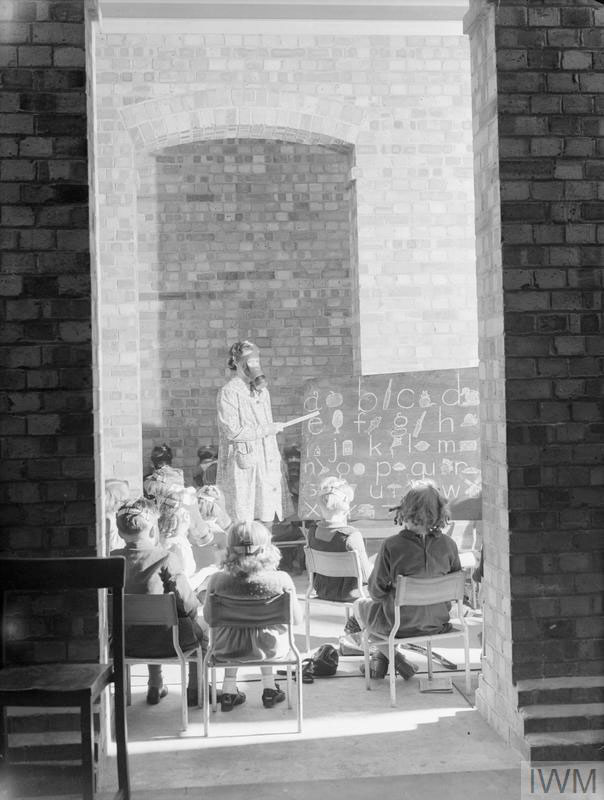

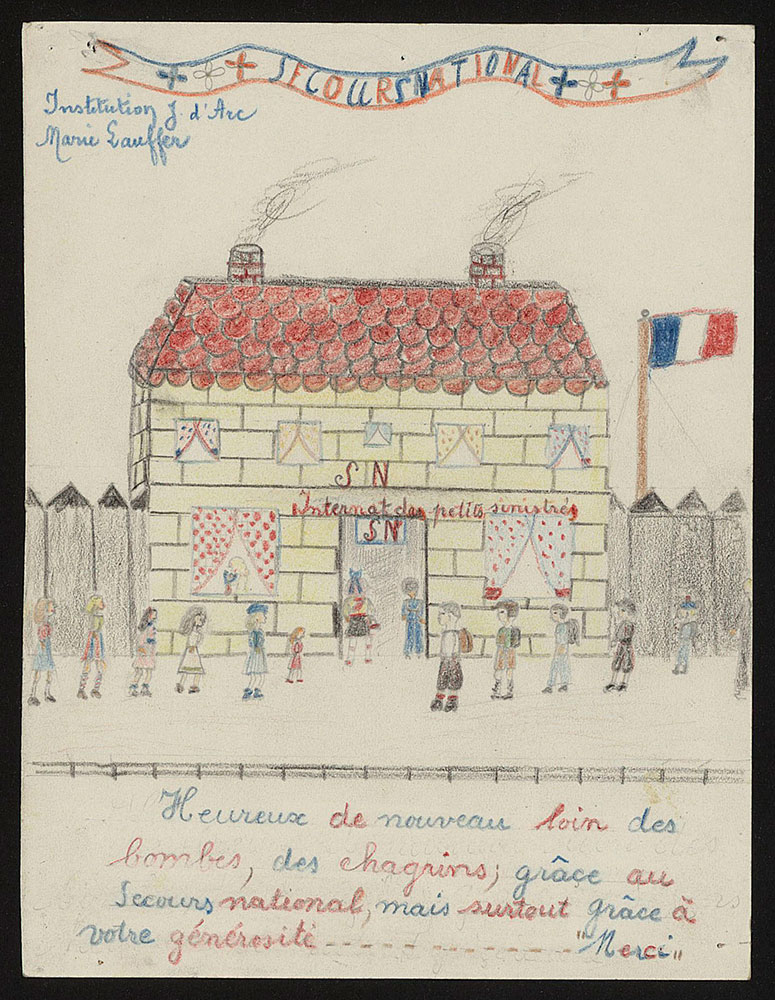

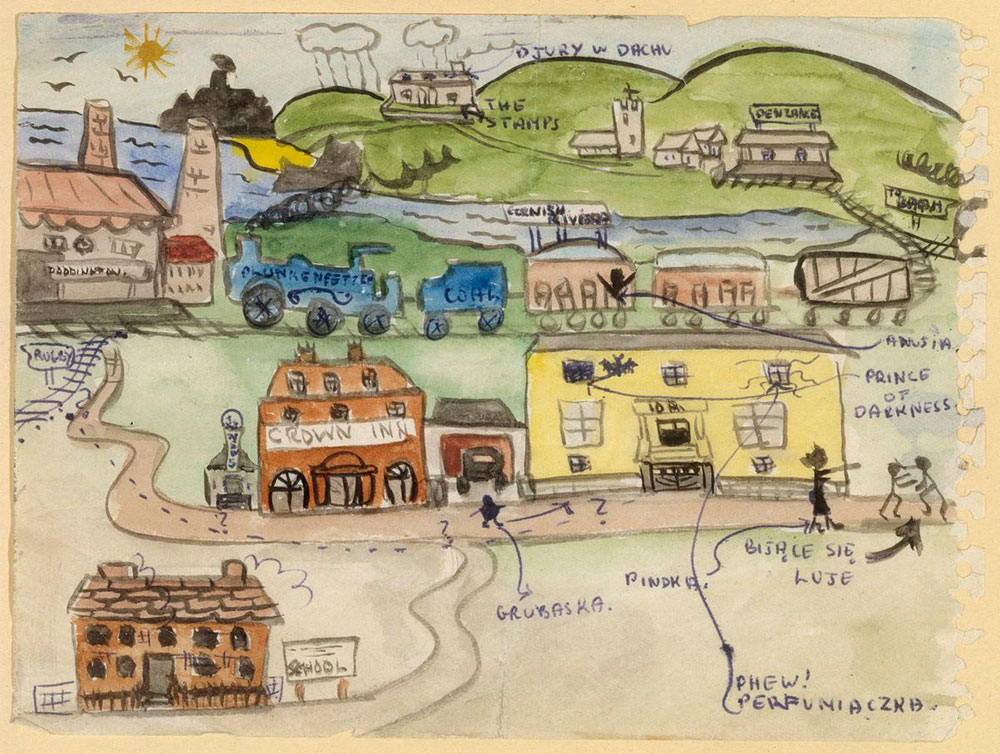

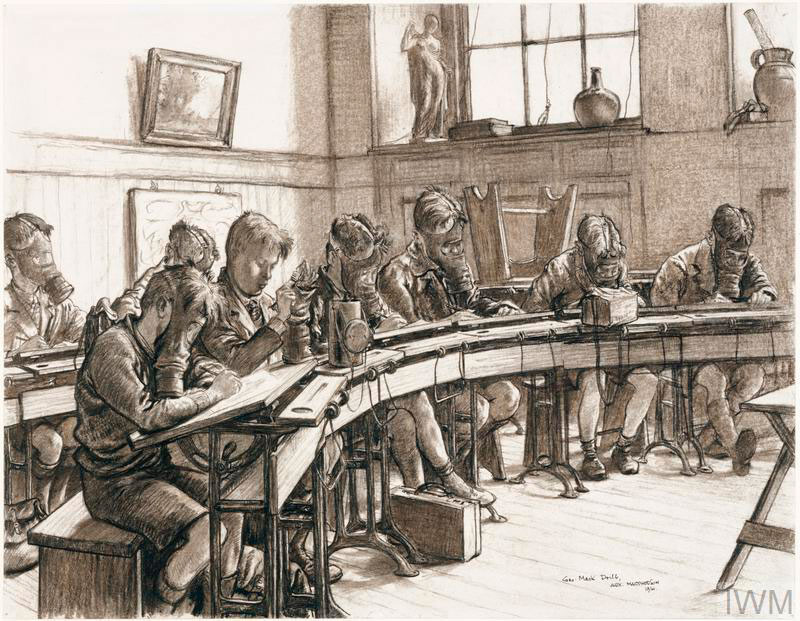

The beginning of the 1939-1940 school year was disrupted by the declaration of war in Western Europe and the displacement of civilian populations. In Great Britain, schools were closed for between one week and three months. Forty-seven percent of the schoolchildren – 637,000 – were evacuated inland and only 300 teachers remained in London, where schools were sometimes requisitioned and used as staging areas for refugees, fire or emergency stations. In France, Belgium, the Netherlands (from May 1940) or Italy (from 1942), schoolchildren were also evacuated and emergency schools were opened, even in internment and concentration camps. As a consequence of the evacuations, in countries such as Denmark, children arriving from Finland faced serious learning difficulties due to the change of language.

In the countries occupied by the German army, one of the measures that most affected children was the restructuring of the educational system. In the words of Heinrich Himmler, it was considered that the non-German population should not have universities and that a four-year school “was enough for them”. In response, secret educational networks were set up in territories such as Ukraine and Poland. Thanks to the Tajna Organizacja Nauczycielska (Secret Teachers’ Organization), approximately 27,000 Polish children graduated between 1939 and 1945. In countries such as Slovenia, the imposition of German – a language the students did not know – changed the academic curriculum. The advance of the fronts and material and food shortages led to the reduction of the school day (France) or the closure of schools (Netherlands). In Greece, the 1941-1942 school year lasted only three months and that of 1942-1943, 20 days.

Educational changes in the war years had in sport and physical activity one of their main manifestations. The desire to create a “strong youth, healthy in body and spirit” led to the imposition of physical education in schools. Youth movements such as the Compagnons de la jeunesse (from the age of 14 to 20), the Hitler Youth or the League of Young German Girls (from the age of 10) or the L’Opera nazionale balilla (from the age of 6) also emphasized the centrality of sport.

During the war, 15,000 primary schools were totally or partially destroyed in France, almost 300 in Belgium and nearly 23,000 in Italy. Austria lost 640 schools and Poland 6,152. In Greece and Yugoslavia, up to 91% and 81% respectively were destroyed. In addition, the fall of authoritarian regimes meant the almost complete reorganization of educational systems, as well as the implementation of projects, such as colonies for children who had suffered violence, based on peace and the construction of a better world.

Work was another of the elements that marked childhood during wartime. The need for manpower and the calls for all the population to make a patriotic effort justified the deployment, both in educational centres and in internment or refuge areas, of various forms of professional training and productive tasks. Due to the prevailing gender roles, this practical education focused, for boys, on manufacturing or, in the case of girls, sewing. In some countries, such as Serbia, a school work service was imposed for teenagers between 14 and 18 years of age. In France, the Centres de Jeunesse model offered housing and a vocational apprenticeship for unemployed young people: in 1944 this program involved 85,000 young people in almost 900 centres.

Compulsory schooling generally lasted until the age of 14, but, due to wartime needs, many boys and girls began to work at the end of elementary school, mainly in agriculture, in the war industry or in services to private individuals. In this sense, childhood was part of what was known as the Home Front. In Great Britain, from 1942 onwards, children over the age of 12 were allowed to work part-time and could be absent from school for up to 20 days a year. In the United States, the employment of teenagers between the ages of 14 and 17 grew by 200% between 1940 and 1944, and 900,000 children between the ages of 12 and 18 worked in violation of the law in their state.

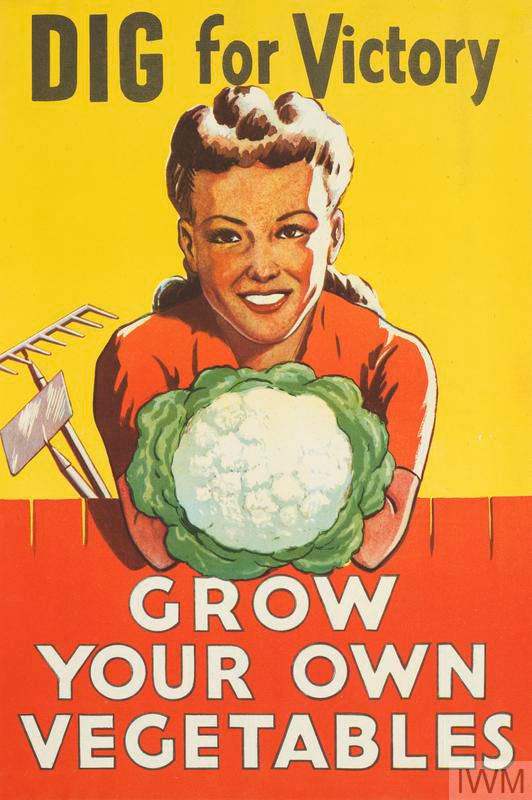

The Dig for Victory campaign illustrates the relevance of agriculture on the home front and the participation of children. Legislation was especially relaxed with regard to the participation of minors in this sector, including work in school and urban gardens, such as the Italian orti di guerra. To these was added their collaboration in private cultivation, where traditionally the entire family labour force was involved. In Germany, in the summer of 1940, school vacations were extended to allow children to collaborate in harvesting the crops. In famine-stricken regions such as Greece, the agricultural labour force stood out for its young age, as could be seen in Manos Zacharias’ 1948 film Les enfants grecs.

In the occupied territories of Eastern Europe, schooling was limited to the age of 14, the age at which children could be required to work as forced labourers. In Poland, the compulsory regulation service of April 1940 was applied from the age of 12. In the case of minors deported with their families, the age was reduced to 10 years and, in the course of the war, this age limit was also applied to transit camps. Women with knowledge of German and “acceptable racial appearance” could be required from the age of 14. Forced labour represents one of the many traumatic experiences of childhood as a consequence of the war.